It was 1942 and comic book creators Charles Biro and Bob Wood had a good

gig and knew it. In an industry rotten with fly-by-night publishers who

disappeared when it was time to cut checks to their artists and

writers, they had the good fortune to be working for Lev Gleason.

Gleason was a progressive sort who offered his talent a share of the

profits, an unheard of gesture at the time. Happy with their work on his

superhero titles Silver Streak and Daredevil, Gleason offered Biro and

Wood the opportunity to develop their own book. A

proposition like this could make the artists wealthy if their title

proved popular.

Brainstorming at a bar one night, Biro recounted

to Wood an unusual story: An unfamiliar man approached him and offered

to arrange what Biro delicately described as an "indiscreet rendezvous"

with a woman. Biro turned down the offer, but his

artist's mind preserved the man's face to memory. He immediately

recognized the face when he saw it the next day in a newspaper. The

mysterious procurer had been arrested for kidnapping the woman he

pitched to Biro the night before. Piqued by this brush with a more

dangerous world, Biro recognized the morbid fascination all of us

possess with the darkness that lay beyond the margins of our everyday

lives. Perhaps a comic that depicted this shadow world would appeal to

readers. Wood was enthused with the idea, and Gleason approved as well.

|

| Another Saturday night downtown. |

In

a purposeful choice to preempt any criticism that their stories were

unrealistically violent, Biro and Wood decided to restrict themselves to

writing about the crimes of actual gangsters and murderers. The title

they devised was another calculated maneuver that allowed them to

denounce the same evils that their lurid illustrations reveled in:

Crime

Does Not Pay. The moral of that adage not withstanding,

Biro and Wood knew that the word "

Crime" did pay. Taking up about a

third of the cover real estate, and dwarfing the predicate "

Does Not

Pay", The all-caps "CRIME" ensured the title would stand out from the

crowded comic book rack.

If the title alone couldn't convince the

reader to spend his dime, the cover art would. Biro was notorious for

filling every inch of the cover with some sort of violence. The first

issue of

Crime Does Not Pay set the standard of mayhem the rest would

follow. In the foreground, one hand stabs another, pinning it to an ace

of spades and the card table below, a gun just out of reach. In the

mid-ground a meaty-faced gangster is cornered against the bar. He holds a

girl in a headlock with his left arm and cradles a submachine gun in

his right. One body is splayed christ-like across the bar. On the

stairs, another man drops his revolver and clutches his chest as he

absorbs a burst of automatic weapon fire. Just for good

measure,

Biro squeezes one more body between the two hands in the foreground. In

the background two men crash through a banister, still grappling

mid-air as they fall to the floor.

|

| Our humble narrator. |

The covers would get even

more explicit, rendering blood and trauma in graphic detail. Instead of

the bloodless chest wound, cop and criminal alike would be cut down by

dripping red headshots. Men, women, young, and old, no one was safe from

the garish four-color torture, beatings, drownings, scaldings shootings

and stabbings. Biro and Wood also introduced a new character, Mr.

Crime, to serve as a sort of spectral narrator. Mr. Crime would float

unseen through the stories, encouraging the wanton mayhem, until finally

turning on the criminal when his inevitable comeuppance arrived.

|

| Blood and gams. |

|

| NOT a manufacturer-endorsed usage. |

|

| subtle... |

|

| The greatest crime in the eyes of 50's cops? Wasting their time. |

|

Knocking out Gramp's teeth is one thing.

But making Grandma cook you a steak?

That's. going. too. far. |

|

| Who can refuse free ice cream? |

|

| If I drew this, I know I'd sign it real big too. |

Within a few years, Crime Does Not Pay's circulation exploded to almost a million issues a month. With the sales of superhero comics headed the opposite way, rival publishers began to lose any distaste they previously had about publishing such bloody and sensational matter. And how did they lose it. With the embargo on bad taste broken, the market was awash in crime titles, each trying to out-shock the other. Crime Does Not Pay's stories were suddenly quaintly obsolete. For the first time, mainstream newsstands carried comics that featured unabashedly twisted and sexually violent plots. Emblematic of this period were the "headlight covers", presenting a scantily-clad, top-heavy heroine, often sadistically restrained in a transparently sexually-charged posture.

|

| "All Top" indeed. |

|

I'm not sure what to focus on here: The missing bra strap?

The reflection running over the edge of the mirror?

Her choice in evening wear, a green tarp?

The fact a mirror that large would shatter

under its own weight? |

|

| No symbolism here. |

|

Not even the paragon of corn-fed American virtue,

Betty Cooper, was safe. |

If the lurid stories and art didn't make it clear enough, the ads for

hernia trusses and home gunsmithing courses should have made it clear

that publishers didn't intend these books for children. But distributors

and retailers didn't segregate their comic titles based on the

audience. There were of course, the strictly under-the-counter or

plain-brown-wrapper mail order adult titles—but parents assumed what was

on the easy-to-reach comic book shelf was appropriate for children.

What they didn't know was retailers were forced by publishers to carry a

fixed menu of their titles, or none at all.

|

Phantom Lady, in particular, was a

favorite target of Wertham. |

In 1954, psychiatrist

Fredric Wertham,

published his highly influential book, Seduction of the Innocent.

Wertham and his published works deserve their own post one day, but the

condensed version is as follows: Wertham conducted or quoted interviews

with individuals who were deemed by the standards of 1954 to by mentally

and/or sexually abhorrent, focusing particularly on adolescents. He

asserted that exposure to "crime comics", a term Wertham had an

unusually broad definition of, had a negative effect on a child's mental

development. Critics would later point out that Wertham's studies were

made at institutions that specialized in children already diagnosed with

behavioral problems. This skewed sample aside, a book-burning moral

panic ensued. Wertham was called to testify before a committee of

Seantors, wringing their hands over the crisis of juvenile delinquency.

The comics industry was strongly encouraged to start policing itself, a

la the Hayes Commission of Hollywood, or risk facing government

censorship. So was born the Comics Code Authority (CCA), a set of rules

that barred anything that may pollute an impressionable child's mind,

from a mild double entendre, to a bloody shootout, to a graphic

depiction a brain-eating zombie's picnic.

|

By the last issue, there was a noticeable

difference in the covers. |

Most publishers saw the writing on the wall, and immediately

dropped their crime titles. Some limped on with their neutered books,

only to fold within the year. EC Comics (another topic deserving its own

post) was particularly hard hit.

Crime Does Not Pay ceased publication

in 1955. Charles Biro left comics entirely to join the advertising

world. Bob Wood however would not find escape that easily.

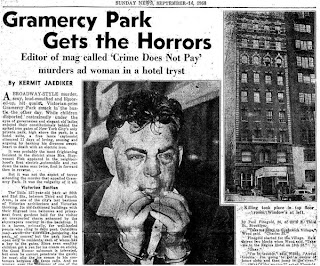

Wood likely had problems with women, money, and drink before

Crime Does

Not Pay, but the cash it brought in, and its ultimate collapse no doubt

exacerbated them. Post-CCA, Wood was reduced to to making sleazy comic

strips for lowbrow and low-rent smut rags. One day in August of 1958,

Wood caught a cab and confessed to the driver he had just killed a woman

who was "giving him a bad time." Wood openly admitted to his crime and

shared his plan to drown himself in the East River after a nap. He even

suggested the cabbie could make a few bucks selling the story to the

newspapers. After dropping off Wood at his hotel, the driver alerted the

police. The cops found Wood in his room, clothes still covered in

blood. He led police to the scene of the crime, where they found,

among the empty bottles, the battered body of a woman. Wood had

bludgeoned her with a steam iron as the coup de grâce of his 11-day

drinking binge. Wood got a shockingly brief 4-5 year sentence for first

degree manslaughter. Released three years later, the stretch in Sing

Sing did little to reform his ways. Unable to repay debts he owed to men

you really,

REALLY don't want to owe debts to, his dispatched corpse

was found dumped just off the Jersey Turnpike in 1962.

No comments:

Post a Comment